Tag: colour LED screens, blue LEDs, physics Nobel 2014

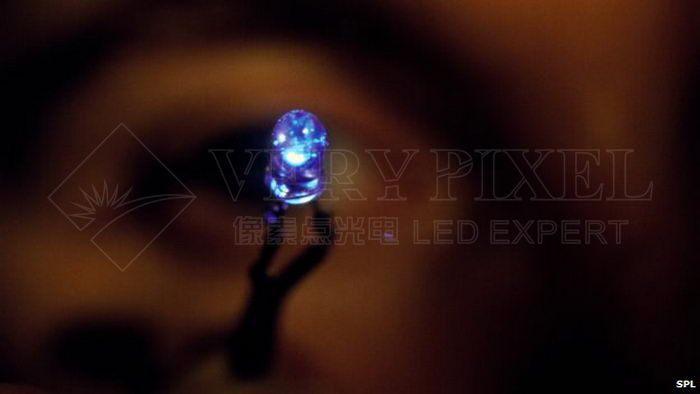

The 2014 Nobel Prize for physics has been awarded to a trio of scientists in Japan and the US for the invention of blue light emitting diodes (LEDs).

Professors Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura made the first blue LEDs in the early 1990s.

This enabled a new generation of bright, energy-efficient white lamps, as well as colour LED screens.

The winners will share prize money of eight million kronor (£0.7m).

They were named at a press conference in Sweden, and join a prestigious list of 196 other Physics laureates recognised since 1901.

Prof Nakamura, who was woken up in Japan to receive the news, told the press conference, "It's unbelievable."

Making the announcement, the Nobel jury emphasised the usefulness of the invention, adding that the Nobel Prizes were established to recognise developments that delivered "the greatest benefit to mankind".

"These uses are what would make Alfred Nobel very happy," said Prof Olle Inganas, a member of the prize committee from Linkoping University.

The committee chair, Prof Per Delsing, from Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg, emphasised the winners' dedication.

"What's fascinating is that a lot of big companies really tried to do this and they failed," he said. "But these guys persisted and they tried and tried again - and eventually they actually succeeded."

Although red and green LEDs had been around for many years, blue LEDs were a long-standing challenge for scientists in both academia and industry.

Without them, the three colours could not be mixed to produce the white light we now see in LED-based computer and TV screens. Furthermore, the high-energy blue light could be used to excite phosphorus and directly produce white light - the basis of the next generation of light bulb.

Today, blue LEDs are found in people's pockets around the world, inside the lights and screens of smartphones.

White LED lamps, meanwhile, deliver light to many offices and households. They use much less energy than both incandescent and fluorescent lamps.

That improvement arises because LEDs convert electricity directly into photons of light, instead of the wasteful mixture of heat and light generated inside traditional, incandescent bulbs. Those bulbs use current to heat a wire filament until it glows, while the gas discharge inside fluorescent lamps also produces both heat and light.

Inside an LED, current is applied to a sandwich of semiconductor materials, which emit a particular wavelength of light depending on the chemical make-up of those materials.

Gallium nitride was the key ingredient used by the Nobel laureates in their ground-breaking blue LEDs. Growing big enough crystals of this compound was the stumbling block that stopped many other researchers - but Profs Akasaki and Amano, working at Nagoya University in Japan, managed to grow them in 1986 on a specially-designed scaffold made partly from sapphire.

Four years later Prof Nakamura made a similar breakthrough, while he was working at the chemical company Nichia. Instead of a special substrate, he used a clever manipulation of temperature to boost the growth of the all-important crystals.

In its award citation, the Nobel committee declared: "Incandescent light bulbs lit the 20th Century; the 21st Century will be lit by LED lamps."

Commenting on the news, the president of the Institute of Physics, Dr Frances Saunders, emphasised that energy-efficient lamps form an important part of the effort to help slow carbon dioxide emissions worldwide.

"With 20% of the world's electricity used for lighting, it's been calculated that optimal use of LED lighting could reduce this to 4%," she said.

"Akasaki, Amano and Nakamura's research has made this possible. This is physics research that is having a direct impact on the grandest of scales, helping protect our environment, as well as turning up in our everyday electronic gadgets."

LED lamps have the potential to help more than 1.5 billion people around the world who do not have access to electricity grids - because they are efficient enough to run on cheap, local solar power.

At the University of Cambridge in the UK, Professor Sir Colin Humphreys also works on gallium nitride technology, including efforts to produce the crystals more cheaply and reduce the cost of LED lamps. He told BBC News he was thrilled by the Nobel announcement.

"It pleases me greatly, because this is good science but it's also useful science. It's making a huge difference to energy savings. And I think some of the Nobel Prizes we have had recently - it will be years, if ever, before that science is usefully applied."

Professor Ian Walmsley, a physicist at Oxford University, said the jury had made a "fantastic choice".

"The ideas derive from some very important underpinning science developed over many years," he said, adding that the technology "makes new devices possible that are having, and will have, a huge impact on society, especially in displays and imaging".

Page address: http://www.verypixel.com/article/show-79.html